Stockholm, April 7th

Architectural Follies

This curatorial phenomenon could refer to works, but it could also refer to floors or pavilions or locations throughout a town; especially when we’re talking biennale. Biennales are contemporary art exhibitions that happen biannually. As you can imagine, they can have a big effect on pushing forward artists’ careers and art movements.

The first one was in Venice in 1895 and had 224,000 visitors. Headed by the mayor, the goal was to become like the World’s Fair for art. They wanted to bring visitors to the city and to talk about what was happening in the arts that was not being represented in museums. They had the council architect make use of abandoned gardens and an artist designed the facade.

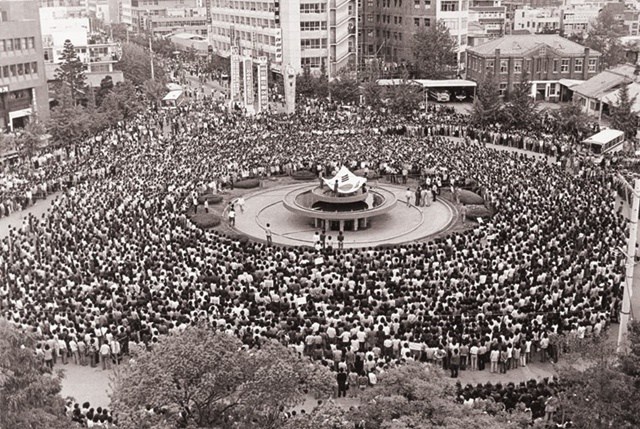

The Eight Climate (What does art do?) biennale takes place in the South Korean city of Gwangju. In 1980 the city became an important and powerful location in the struggle for democracy. Peaceful demonstrations were suppressed by military forces, leading to the violent massacre of civilians. The biennale was founded in the spirit of the Gwangju Democratization Movement.

In this article, I would like to explore the off-site project spaces instead. Removed from the confines of the hall, I found that these locations provided unique situations for artistic commissions.

Throughout the years, the Gwangju Biennale has worked with different regional and local institutions. The Mudeung Museum of Contemporary art, Uijae Museum, Gwangju Museum of Art, and the Nine Gallery were each involved in this biennale, presenting commissioned works off-site from the main exhibition.

A new project called Gwangju Folly started in 2011 under the direction of Seung Hyo-sang and Ai Weiwei. The long term aim of the project is to connect several spots in the city, creating a coherent constellation of spaces by using the morphology of the city as a new autonomous exhibition material.

Re-routing roundabouts

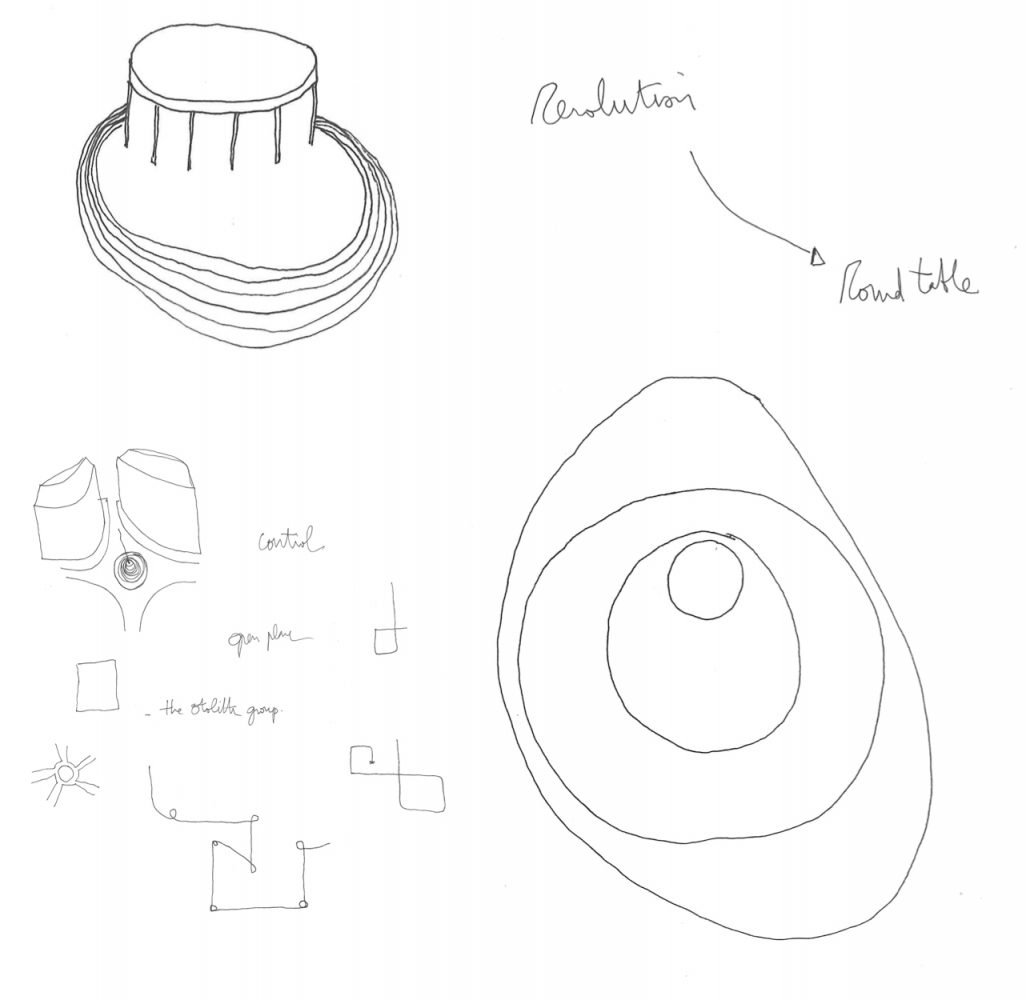

I had the opportunity to speak with German architect and curator Nikolaus Hirsch about the Roundabout Revolution folly built in 2013 by Eyal Weizman (Israel) and Samaneh Moafi (Iran/Australia). This talk was mainly focused on the importance of the autonomous format of such a structure.

The project took place in the traffic circle where people gathered in 1980 during the political uprising. This urban space has since been renovated with a new train station, erasing the morphology of the past. In order to leave a memory in that space and question the circle’s usage, the architect built a little round pavilion, where people can sit around a table and look and contemplate the history of that space.

Surrounding the pavilion, where cars pass over the location of the former roundabout, the architect painted on the street surface the former shape of the traffic circle. This drawing depicts, in concentric rings, different iconic public squares, such as that of the Arab Spring, Tahrir Square in Cairo and Jaleh Square in Tehran. Juxtaposing these different points of organised resistance, the architect creates a subtle reflexion on monument making.

Whereas in Arab countries the public square has transformed from being a strong symbol of revolution to the site of oppression, in Gwangju, by contrast, these squares have either been deleted or nearly eliminated through remodelling and renovation for new urban development.

Instead of building an actual monument in memory of this protest, here we see a form, which embodies a sort of “soft monument”.

The aim for the follies in Gwangju seems to be focused on creating places of culture and education rather than building monuments in a traditional sense.

This investigation of the public space is interesting because it is a way to rebuild the story of the uprising in South Korea, by offering a space to document history and generate conversation among people.

Jérôme Malpel, September 2016, for Curator Lab